Just as “Sirāt” is a twisty thriller that takes you unexpected places on its tragic journey into the dystopian desert unknown, the heady filmmaker behind it, Oliver Laxe, is not your average interview. His fourth European feature, “Sirāt” is his breakout: It wowed critics at Cannes, shared the Jury prize, and won the Cannes Soundtrack Award for Best Composer for Kangding Ray.

Neon picked up “Sirāt” as one of the company’s five international features vying for a slot in the final Oscar five. I’ll wager the movie will wow the stateside arthouse box office as it has France and Spain and four other countries (worldwide gross: $9 million). Audiences have never seen anything like it. (IndieWire’s critics poll voted “Sirāt” the best film in Cannes.)

This shocking piece of cinema is best left undiscussed. The less you know about it going in, the better. The French-Spanish-Galician filmmaker is begging folks not to share its secrets.

For context, the movie starts at a rave in North Africa: Huge speakers amplify the booming beat against looming cliffs as ravers dance in delirious abandon. Winding through the crowd is a Spanish father (Sergi López), his son, and his dog. They are doggedly searching for their missing daughter/sister, who has left home to follow rave culture. As the military arrives and shuts down the rave and directs traffic away, the family jumps into their car to follow a caravan into the mountains. They befriend a small commune of nomadic ravers seeking their next high. Somewhere in the distance, a war is raging. As the group drives into more rigorous and remote areas, they band together to survive the obstructions coming their way.

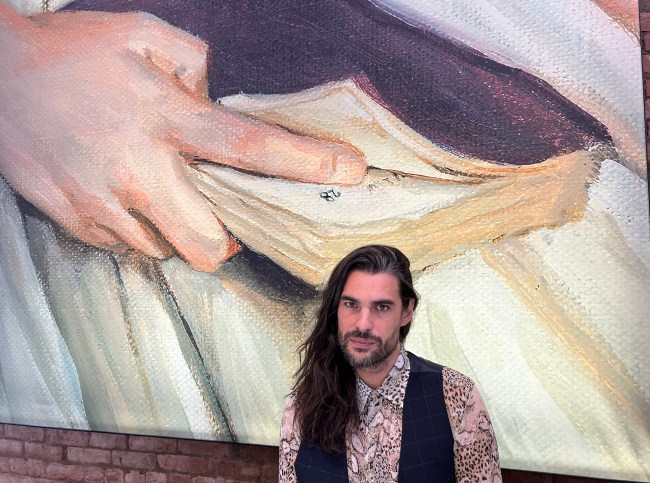

We met at Neon’s offices in New York, as Laxe, 43, sincerely lays out his filmmaking philosophy. “For me, the ontology of cinema [is] images,” he said. “If a film is connecting with people, it is because, in my films, in terms of proportions, there is a spiritual geometry in my images. They are connected with my unconscious and with the collective unconscious.”

Why is the movie reaching so many audiences? “The film is a medicine,” he said. “Sometimes, when it doesn’t taste good, we put honey on the edge of the glass [so that] it’s sweeter. People think the film is sexy, for the music, the techno. A lot of young people are coming in France, youngsters are watching, are connected with the film. That was one of my intentions: to make a film for young audiences, to invite them to come to the film theater.”

No question, Laxe takes his filmmaking seriously, on many levels. During the writing and pre-production process, he struggles to be strong enough to protect his fragility, he said, so that “the images arrive alive at the end in the edit process. I’m sorry to say, but most images, nowadays in cinema, they have too much weight, because images are used to say something, to tell something. And they don’t. They are not alive anymore.”

The reason “Sirāt” has so much force: “Our images can penetrate the human metabolism because they are still not domesticated,” he said. “Filmmakers have to know where, when to stop. We have to stop at the right time in order to not put too much weight into the images. And David Lynch was an expert on this: He’s still the guy who knew how to keep this unconscious imagery, all our fears, all our desires, all our dreams, all our nightmares. I’m making sorcery like him.”

Of course, Laxe studied “The Wages of Fear” and “Sorcerer” when preparing to shoot his hazardous North African road movie. But the movie is more than just road scares. “‘Sirāt’ has three dimensions,” he said. “The physical dimension, the physical adventure. That’s where these films and ‘Mad Max’ are dialoguing with ‘Sirāt,’ or we are dialoguing with them. We were joking that we were making ‘Mad Max Zero,’ the pre-apocalypse. But these films, they are not much existential or transcendental.”

That brings the next dimension. “There is another layer that is existential,” he said. “And for this dimension, we were inspired about American movies from the ’70s: “Vanishing Point,” “Two Lane Blacktop,” “Apocalypse Now,” “Easy Rider.” All these films, we don’t know what they are about, but they were expressing the fears and the desire of the American society in the ’70s, and we can feel all the energy of this decade, the angst. This is powerful. That’s why we want to make films: We want to be connected with our time.”

And the third dimension? “That is the more metaphysical,” said Laxe. “For me, obviously, my master is [Andrei] Tarkovsky, and in particular, for ‘Sirāt,’ was ‘Stalker’ and ‘Nostalgia.’”

“Sirāt” is filmed in Super 16mm. “Chemistry,” he said. “My purpose is to make images that will be with a spectator after watching the film for a long time. It’s better to work with this alchemy. Obviously, after the film, art is digitalized … a digital image can also penetrate a spectator, but not at the same level. There is imperfection. It. Art is about mistakes.”

The sound design, meanwhile, is extraordinary, especially at the start of the film, when Laxe mounts a rave in the desert, surrounded by massive cliffs. “I discovered that I’m a musician making this film. For the first time I had the opportunity to work with a musician, Kangding Ray, before the shooting for one year and a half. We went to shoot with most of the music. The idea was to build a sound landscape, to watch the sound and to hear the image.”

After living in Morocco for more than a decade, Laxe absorbed his surroundings. “I see all this landscape, with all this erosion, all this violence,” he said. “This erosion is made by the snow, by the wind. We feel small. In ‘Sirāt,’ it works like this. We are in the mountain, so we feel that we are small. We are nothing, and we go to the desert. The mountain in Morocco is existentialist. ‘Who am I, what I’m doing here? I will die. I’m nothing.’ The desert is this abstract space where human beings cannot hide ourselves. We have to look inside. We look to the sky.”

As the caravan climbs into more precarious terrain, they have to overcome each obstacle thrown their way. Laxe loves to shoot in nature, “not because nature is beautiful,” he said. “It’s because nature is a manifestation of this creative intelligence that is behind things, call it God. So to shoot in nature, nature is manifesting. I like limits, as a human being, as a filmmaker. I like to be tested by nature, because I like to surrender myself to this, because I know that even if it shakes me, it is taking care of me. Life doesn’t give you what you are looking for. No, life gives you what you need. And there is a difference between one and the other, and that’s why human beings are, from time to time, frustrated. That’s why filmmaking is frustrating, because we are looking for something. But life is shaking you, giving you what you need. That’s why my films are really risky.”

In order to cast the film’s motley crew, Laxe turned not only to lauded actor Lopez, but some non-pros, friends he’s known for years. “Bigui [Richard Bellamy] was a friend from 15 years ago,” he said. “He’s on the script since the beginning when I’m writing. He’s a poet. He’s a Peter Pan. He lost his hand three years before the shooting. I had doubts if I [would] shoot him or not, because we already had someone who doesn’t have legs. I don’t like when you feel the intentions of the filmmaker: The filmmaker has to hide the proof of the crime. So I was afraid of having two people with deficiencies… At the end, I accepted that. I mean, I love them. I wanted them on my film. So I assume the consequences. It worked. It’s life who wanted them on the film, because at the end, it’s a film about the wound, about the pain of the war today.”

By using non-actors who have endured the vicissitudes of the world, Laxe didn’t have to develop the characters in a conventional way. “People watch too [many] series, so they are used to how the characters, the plots are developed,” he said. “But I don’t need this. My images say things and evoke things. I don’t need to develop the characters. You feel their gesture, their silence, their scars. Do you feel their wound exactly? You feel their soul. What else do you want we express about them?”

“Sirāt” feels like a message from the future. At the end of the film, a train appears, carrying refugees across the arid landscape. “This train is the future,” said Laxe, “[carrying] human beings, from different regions and races. We will go on the same train; we will be pushed. It’s difficult for us to change. The only hope is that life will oblige us to change. Life will push us to a limit, to an edge that we will be obliged to ask ourselves, ‘What is it to be human? Climate change, artificial intelligence, what is it to be human?’ The answer will be: more human. I have a lot of hope.”

Neon will release “Sirāt” in New York and Los Angeles on Friday, November 14.