How researchers can define quality, guide prompts, and shape the value of AI outputs.

AI agents, synthetic users, deep research, staying relevant as a UX researcher can feel like a challenge that resets every week. Teams across product, design, and engineering are moving faster than ever, often powered by the same underlying AI technologies. Prompt engineering and system design have quickly become central topics across disciplines, raising a familiar, and uncomfortable, question: where does UX research fit now?

My experience building LLM-based products over the past two years has led me to a clear conclusion. This moment is not the end of UX research. It is the same work we have always done, understanding people, defining value, but applied to a new class of systems. And for researchers willing to adapt, it creates an opportunity to move upstream and become more strategic than ever. As products become cheaper to build and AI spreads across nearly every workflow, teams now face a new foundational decision: how much AI should this feature contain?

When the answer is “yes”, and it is not always, the work does not stop there. A second, equally important question follows: what form should that AI take? One of the most prescient frameworks in this space comes from Jake Saper and Jessica Cohen at Emergence Capital, who describe AI products along a spectrum. On one end are pure chat-based systems that maximize flexibility. On the other are AI-enhanced features that trade flexibility for simplicity. Most production features live closer to the latter. The product defines the prompt, sometimes with light user input, and delivers the output in a predetermined format. Every “summarize,” “rewrite,” or “generate” button we encounter today reflects this tradeoff.

Delivering value with AI enhanced features means having a solid understanding of what the user is attempting to achieve within the context of their workflow both for the actual output and the design of how it is delivered. Take for example, a summarize feature. A summary can mean many different things depending on where it is being delivered. A “Summarize” button offered in Gmail likely needs punchy and bulleted contents. The same within Adobe acrobat for a large PDF could mean a multi paragraph executive summary. It is all about context and the actual need in the moment. The same we have always been doing but new.

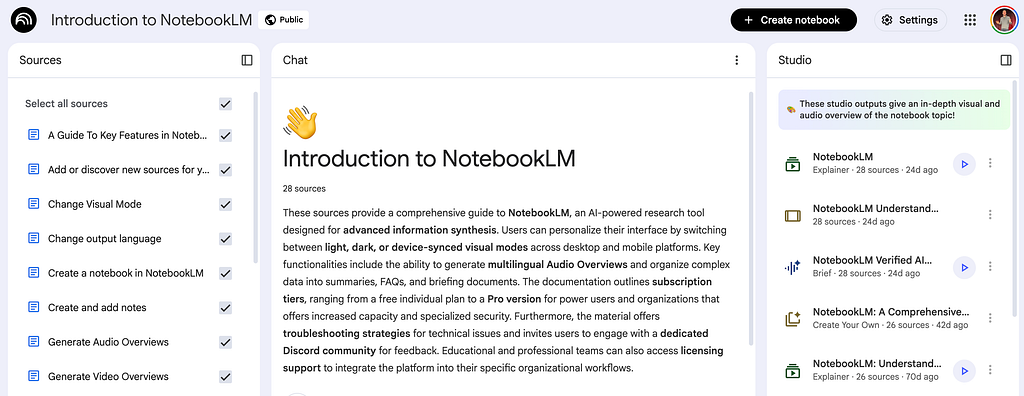

NotebookLM offers a compelling example of this shift. The product began as a chat-based, retrieval-augmented system. It gained widespread attention with its audio overview feature, which generated a podcast-style summary of a user’s materials, no prompting required. That feature delivered immediate, differentiated value by meeting a specific user need in a novel format. While the initial novelty has faded, subsequent updates have reinforced NotebookLM’s position as a model for AI-enhanced productivity.

The Studio feature set within NotebookLM illustrates the pattern particularly well. Users are presented with a set of structured options that guide them toward generating reports, briefs, or analyses. The real power lies not in unrestricted chat, but in the ability to lightly customize a pre-generated prompt. In Emergence Capital’s terms, this is a true copilot: a system that helps users provide the right input in order to receive a valuable output. When a user asks NotebookLM to generate a report, success is not defined by grammatical correctness or factual accuracy alone. Success is whether the output fits the user’s actual need, whether it advances their task, supports their workflow, or deepens their understanding.

This is where the role of UX research begins to change… not in kind, but in scope.

A New Way to Create Value

Creating value with LLM-based features is not about writing the cleverest prompt. It is about defining the right instructions so the system produces something that is genuinely useful to the user in that moment. Prompt quality matters, but prompts do not exist in a vacuum. They sit at the intersection of engineering, design, and, critically, research.

NotebookLM’s opening chat response is a useful example. As a user logs in, the chat window is filled with an overview of all contents that helps users make sense of their materials as soon as they open a notebook, reducing the cognitive cost of re-orienting themselves. Engineering work was required to craft prompts that reliably surface the right insights. Design work was required to decide how that information should appear on the page. But neither of those efforts can succeed without first understanding what users actually need at the moment of entry. That understanding is where research does its most important work, informing both what the system should generate and how that output should be presented.

Design guidance for displaying AI-generated content is relatively well covered. Many strong frameworks already exist for structuring text, surfacing key information, and presenting outputs in ways that are readable and actionable. What has received far less attention is the upstream work of shaping the instructions that guide generation in the first place. Ensuring a prompt is directionally correct — aligned to real user needs rather than abstract capabilities, was always important. With LLMs, it becomes foundational.

This is where UX research creates new leverage. By engaging early, researchers can help teams anchor feature development in what is actually possible given both the state of the technology and the user’s needs in context. In my experience, this approach consistently opens up more promising product directions. Instead of retrofitting research onto an already-defined solution, teams start with a shared understanding of value, giving design and engineering a clearer target to aim for as they build.

A New Process for Defining Quality in Outputs

For decades, UX research has focused on identifying the user needs a product must satisfy. That part of the work is unchanged. What is new is the nature of the systems we are designing. With large language models, teams no longer have complete control over outputs. These systems are inherently non-deterministic, we can guide them, but we cannot fully dictate what they will produce.

In traditional product design, many needs could be satisfied with deterministic solutions. When Apple realized people were using their iPhones as flashlights, the solution was straightforward: a single button that produced a single, predictable outcome. One tap, immediate value. No ambiguity, no interpretation required. That model works well when the need is simple and the desired outcome is clear.

As needs become more complex, so does the solution. Uber faced a different problem: passengers felt anxious while waiting for their ride. The company could not control the behavior of individual drivers, so instead it designed an experience to manage uncertainty. A live map showed the driver’s progress (although not always truthfully). Messaging explained potential delays. Contact options gave users a sense of agency. Each element addressed the same underlying issue, negative sentiment during the wait, even though the core system remained unpredictable.

Working with LLMs is similar, but amplified. An LLM behaves less like a traditional interface and more like a human collaborator: responsive, capable, and inconsistent. It may produce insightful results one moment and confident-sounding nonsense the next. This unpredictability is not a flaw; it is a property of the technology. The challenge, then, is not eliminating variability, but maximizing output quality despite it.

That challenge requires a different approach. Rather than treating quality as an after-the-fact judgment, teams must define what “good” looks like in advance, and do so in a way that acknowledges uncertainty. This is where UX research plays a central role: translating user needs into clear quality signals that can guide generation, evaluation, and ongoing refinement, even when outputs cannot be fully controlled. Here is how I got about it.

Surfacing Quality Signals

The first step is establishing a shared understanding of what constitutes a high-quality experience. When a user requests a briefing document in NotebookLM, what are they actually expecting to see? The answer is inherently subjective. Different users bring different expectations, shaped by their goals, context, and prior experience.

This is why qualitative research is essential. In-depth interviews allow teams to understand not just what users say they want, but how they judge AI-generated outputs in practice. I start by asking users to share what they expect to see as an output. Afterwards, I walk them through examples, either outputs they already use or ones I introduce, and have them describe what they mean when they say something “informs,” “summarizes,” or “provides direction.” These conversations reveal the mental models users bring to AI systems and the tradeoffs they are willing to make.

As classic Jobs to Be Done research has shown, people are rarely asking for features in the abstract, they are trying to make progress in a specific situation. The same principle applies here. With that mindset, research becomes a game of identifying the main themes in what users are asking for in the output.

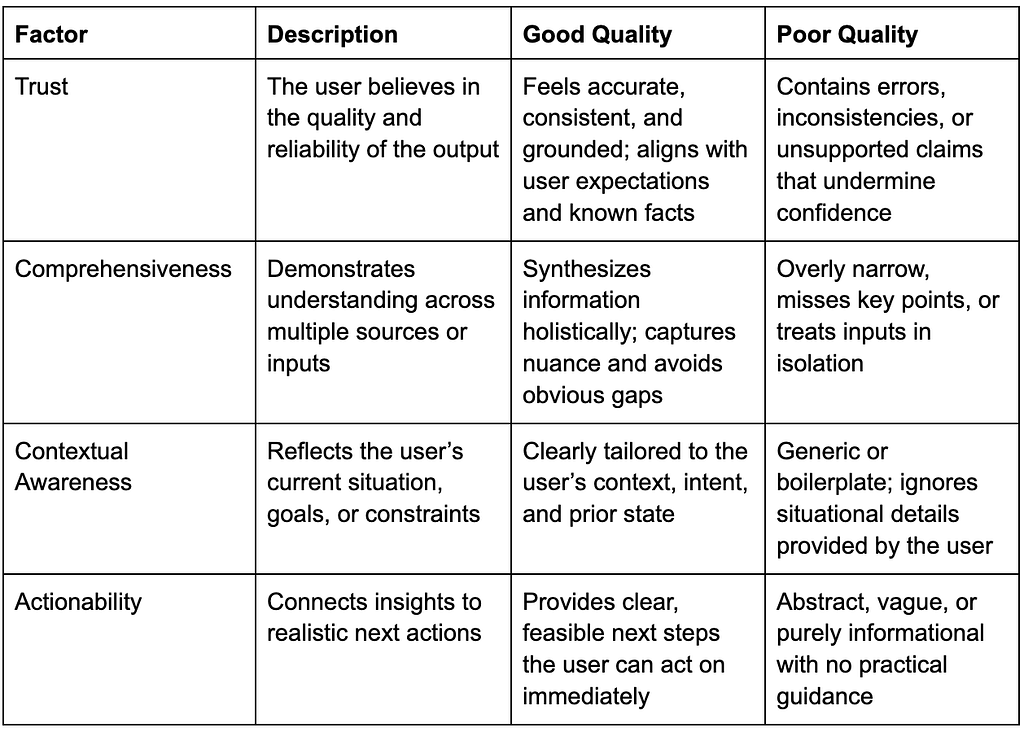

In the case of NotebookLM, early qualitative work might surface themes such as trust, cognitive relief, contextual relevance, and actionability. Users may not articulate all of these dimensions explicitly, but patterns emerge across interviews. A useful heuristic here is the 80/20 rule: a relatively small set of research-derived criteria can account for the majority of users’ expectations.

For example, a high-quality briefing report in Notebook might be judged on whether it:

- Feels trustworthy

- Demonstrates understanding across multiple sources

- Reflects the user’s current context

- Connects insights to realistic next actions

Validation and Refinement

Once core quality themes are identified, the next step is validation and refinement at scale. Surveys are particularly effective here. They allow teams to translate high-level themes into more specific, testable factors and to understand how consistently those factors matter across users and contexts. When designing these studies, I ask participants to evaluate outputs that closely resemble what the product would actually generate. Users are then asked to rate and critique those outputs, providing nuance around what makes them useful, or not.

Take trust as an example. Users frequently say they want AI outputs they can trust, but trust is not a single, universal attribute. At a minimum, it implies factual correctness. Beyond that, trust is shaped by tone, length, structure, and framing, all of which vary by context. An email summary should be concise and direct. An executive briefing should surface key themes and unexpected insights. A call recap should highlight action items and mention relevant stakeholders. When an output matches what users expect in that situation, trust follows.

Surveys help teams refine these distinctions. In the NotebookLM case, researchers might explore when users feel a pre-created executive briefing demonstrates contextual awareness and when it does not. For example, users may respond positively when recent meetings or emails are incorporated appropriately, and negatively when outdated or irrelevant documents are surfaced. This level of specificity is critical, it directly informs how prompts should be written and constrained.

Creating a Quality Rubric

With qualitative depth and survey validation in place, the next step is synthesizing insights into a shared quality rubric. There is an immediate opportunity for the engineering team to create refinement, yet as previously suggested, it is not just about the actual output but how it is designed. As such, this rubric can become the centering focus for the entire team.

A well-designed rubric defines each quality factor clearly, illustrates what good and poor outputs look like, and makes tradeoffs explicit. It allows designers, product managers, and engineers to align on what success means and how it should be evaluated. Importantly, it translates research insights into something actionable.

For prompt engineers, the rubric serves as a definition of the global maximum, the set of characteristics the system should optimize for overall. Prompt iteration can then focus on finding local maxima within that boundary, confident that improvements are aligned with real user needs rather than proxy metrics.

Continued Refinement

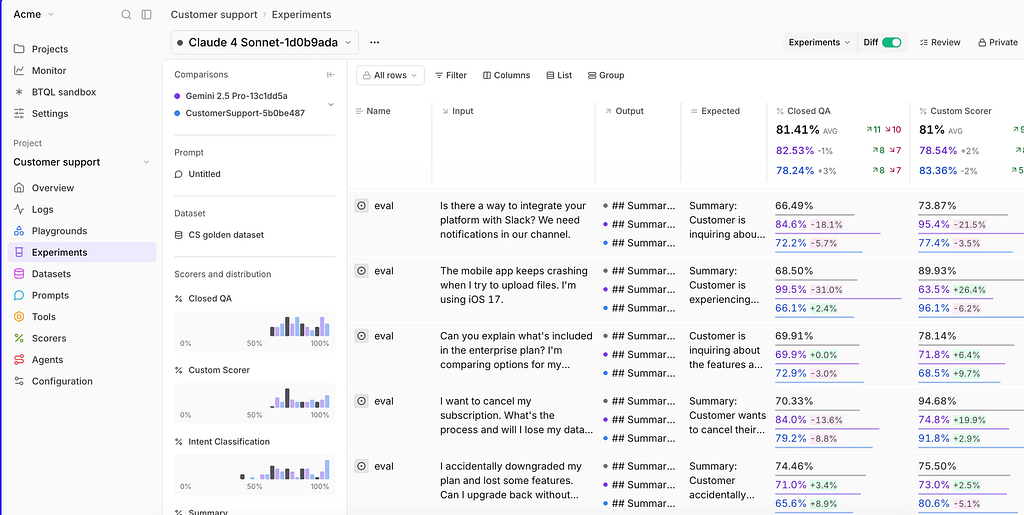

Even with a strong rubric and well-crafted prompts, the work does not end. Many teams now rely on AI-based testing and automated evaluation to refine LLM outputs over time. Companies such as BrainTrust have built extensive platforms that allow product teams to test the output of their prompts at scale, across models. Leveraging these tools are far more effective when grounded in research-defined quality criteria.

A solid rubric ensures that synthetic user testing, automated scoring, and iterative refinement are anchored in metrics that matter to real people. Rather than optimizing loosely connected signals, teams can focus on outcomes that genuinely improve the user experience.

This ongoing refinement is especially important in a fast-moving market. User expectations are evolving quickly as the Overton window of what is possible with AI continues to shift. A bullet-point summary that felt impressive yesterday may be table stakes today, replaced by audio, visual, or personalized formats tomorrow. Quality rubrics must be revisited and updated as expectations change, creating a sustained, strategic role for UX research in keeping AI systems aligned with human value.

UX Research as the Interpreter of Human Value

The science of UX research has not changed. People are still complex, contextual, and inconsistent, and understanding what they need remains the core of the work. The methods have not changed either. UX researchers are still experts at learning from users, identifying patterns, and translating insight into action.

What has changed is the nature of the systems we are shaping. With LLM-based products, outputs are no longer guaranteed, and a new stakeholder, the prompt engineer, has entered the room. Research now has a direct line into how AI systems are instructed, evaluated, and scaled. Insights no longer stop at informing interfaces or features; they define the criteria by which machine-generated work is judged as successful.

This process is not foreign to UX research, but the leverage it creates is new. By defining quality up front, researchers can shape how intelligence itself is tuned, guiding optimization, grounding automation, and ensuring that faster iteration does not come at the expense of human value. In my own work, this shift has made the field feel more relevant and more exciting than it has in years.

Done well, UX research can become the discipline that defines what people want from AI systems, and holds those systems accountable to real outcomes. AI will continue to do more of the work. That is not changing. What can change is whether that work actually matters. UX research is uniquely positioned to make sure it does.

Same, but new: UX Research in the age of LLMs was originally published in UX Collective on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.